This weekend, as we witness a lunar eclipse…the longest of the century…we celebrate a great event of the 20th Century…an event that helped Rock ‘n’ Roll cement itself as an American art form. No, it was not on Nov 20, 1973 when an inebriated Keith Moon passed out on his drum kit during The Who’s performance at the Cow Palace and had to be replaced by a fan in the audience (but that is definitely something of legend). No. It is when Bo Diddley appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show on the same day but in the year 1955.

Diddley had just released his first record and damn if his fresh sound was something that had never been heard before. He played an open-tuned guitar with the rhythm of a washboard player…his guitar vibrating to his tremolo effect, with maraca player sensation Jerome Green in lock step in the background and those jungle drums helping work the sound out. It was nothing…it IS nothing…that had been heard or seen before. And with his entrance onto the scene, came the invitation to be on the Ed Sullivan Show, which was watched far and wide across the United States.

The story of Bo on Ed gets complicated. It seems that during a practice run on show-day, Bo was riffing on Sixteen Tons, a song that had been a hit for country artist Ernie Ford. Sullivan asked Bo to play that song on the show. And while Diddley seemed to agree, he ended up hitting the stage playing his namesake song, which was the real single from his new record anyway. There is the story where Diddly thought he was supposed to play BOTH songs, which seems like a stretch to me. Regardless, Bo Diddley and band hit the stage, electrified a nation with his rendition of Bo Diddley and was subsequently banned from The Ed Sullivan Show because of it.

But the lightening was out of the bottle, and to this day, we can all appreciate the moment when Bo Diddley helped usher in the era of Rock ‘n’ Roll to a generation who was begging for it.

The Beaver Moon partial lunar eclipse on Nov. 19 will be the longest of the century.

Time to stay up late tonight to see if a clear sky will allow you to see the longest lunar eclipse of the century.

2021 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD WINNERS ANNOUNCED

The winners and the others listed are here. I had never known the actual mission of the National Book Awards/Foundation until reading the beginning of this article this morning, and for me…it totally fulfills it, being a place of discovery every year about books that I had no idea about: “The mission of the National Book Foundation is to celebrate the best literature in America, expand its audience, and ensure that books have a prominent place in American culture.”

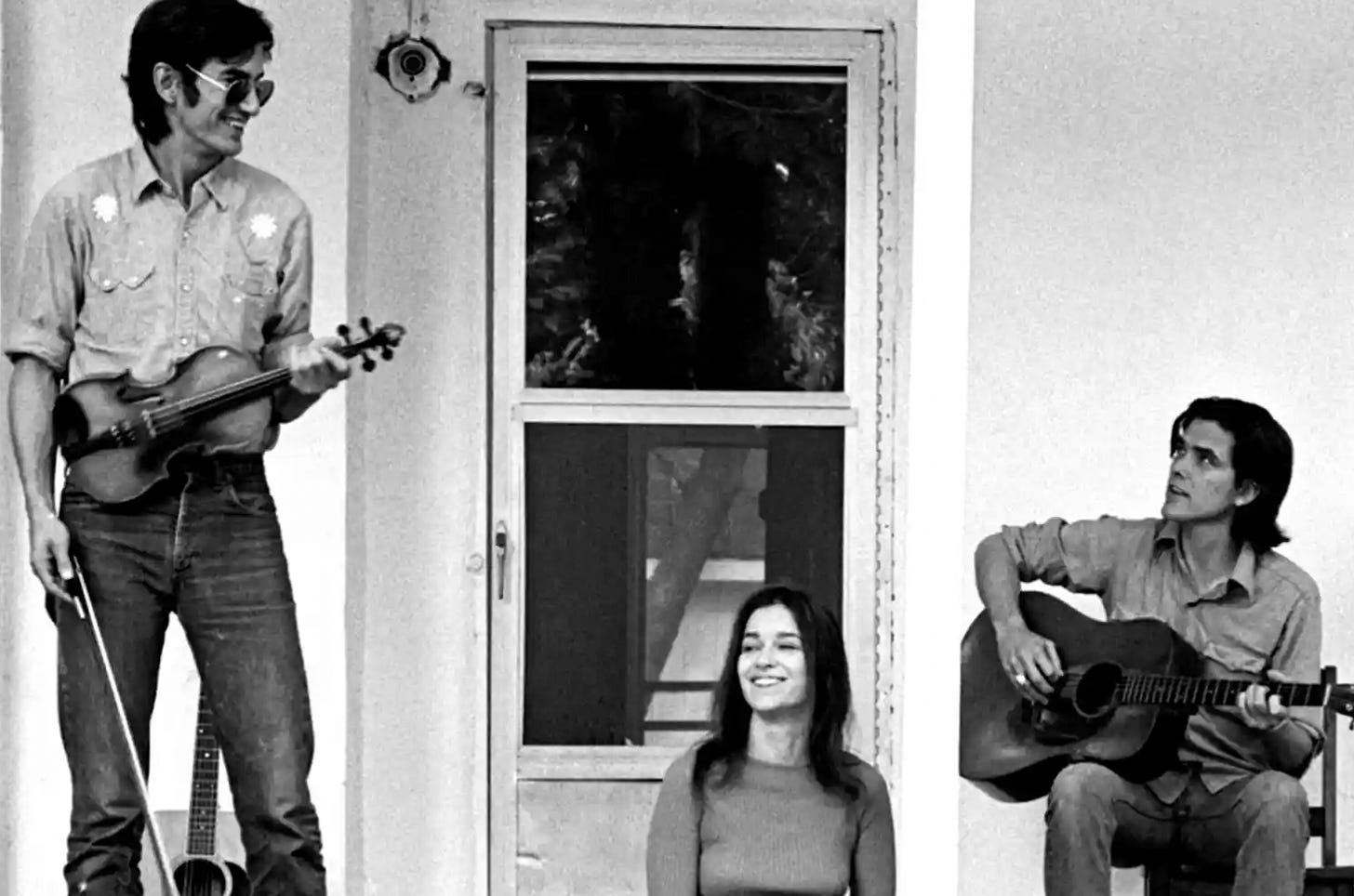

‘You can’t separate them’: the unlikely love story of Guy Clark, Susanna Clark and Townes Van Zandt

“The unusual bond between the three musicians is the focus of a new documentary Without Getting Killed or Caught, a story of romance, creativity and tragedy.”

Ron English and 1XRUN Team For Massive NFT Collection

I love the work of Ron English and how he plays with the brands and cultural icons that threaten to define us. His entry into the NFT space makes the whole space more exciting to me He is focusing on lightbulbs here: “Each Bulb represents an idea: the foundation for creativity.” (or is it flipping a bird to this BIG NFT idea?).

WEEKEND LISTEN: Lament in a Deep Style 1929-1931 (Kitsos Harisiadis)

My friend Roe Peterhans at Third Man Records gave me this beautiful time capsule, lovingly put together by ethnomusicologist Christopher King with cover drawing by R. Crumb. I know King’s work through his Tompkins Square releases (the Imaginational Anthem Vol. 6 is a big time favorite). His latest series with Third Man Records is equally astounding (the newest being How The River Ganges Flows, which I need to get on vinyl!). Lament in a Deep Style is a look into how one artist seemed to have a mastery over a Greek mountain style of music from the early 20th century. Harisiadis transforms the clarinet into a magical voice, hypnotically swimming over his accompanying instruments. The deep researched liner notes help introduce the listener to the mirologi, a “formless dark thing, a mediation” that is a pretty spell-binding listen. Painstakingly mastered by King, Chris Leva and Bryan Hoffa, this record is an epic film within its grooves…a real trip through the past.

Martín Espada won the National Book Award this past week for his latest book of poetry, “Floaters”. The poem that grace’s the book’s title was triggered by a photo of a father and young son found drowned on the bank of the Rio Grand in Mexico, which they attempted to swim across to get to Texas…

Floaters

By: Martín Espada

Ok, I'm gonna go ahead and ask ... have ya'll ever seen floaters this clean. I'mnot trying to be an a$$ but I HAVE NEVER SEEN FLOATERS LIKE THIS,could this be another edited photo. We've all seen the dems and liberal partiesdo some pretty sick things.—Anonymous post, "I'm 10-15" Border Patrol Facebook group

Like a beer bottle thrown into the river by a boy too drunk to cry,

like the shard of a Styrofoam cup drained of coffee brown as the river,

like the plank of a fishing boat broken in half by the river, the dead float.

And the dead have a name: floaters, say the men of the Border Patrol,

keeping watch all night by the river, hearts pumping coffee as they say

the word floaters, soft as a bubble, hard as a shoe as it nudges the body,

to see if it breathes, to see if it moans, to see if it sits up and speaks.

And the dead have names, a feast day parade of names, names that

dress all in red, names that twirl skirts, names that blow whistles,

names that shake rattles, names that sing in praise of the saints:

Say Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez. Say Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos.

See how they rise off the tongue, the calling of bird to bird somewhere

in the trees above our heads, trilling in the dark heart of the leaves.

Say what we know of them now they are dead: Óscar slapped dough

for pizza with oven-blistered fingers. Daughter Valeria sang, banging

a toy guitar. He slipped free of the apron he wore in the blast of the oven,

sold the motorcycle he would kick till it sputtered to life, counted off

pesos for the journey across the river, and the last of his twenty-five

years, and the last of her twenty-three months. There is another name

that beats its wings in the heart of the trees: Say Tania Vanessa Ávalos,

Óscar's wife and Valeria's mother, the witness stumbling along the river.

Now their names rise off her tongue: Say Óscar y Valeria. He swam

from Matamoros across to Brownsville, the girl slung around his neck,

stood her in the weeds on the Texas side of the river, swore to return

with her mother in hand, turning his back as fathers do who later say:

I turned around and she was gone. In the time it takes for a bird to hop

from branch to branch, Valeria jumped in the river after her father.

Maybe he called out her name as he swept her up from the river;

maybe the river drowned out his voice as the water swept them away.

Tania called out the names of the saints, but the saints drowsed

in the stupor of birds in the dark, their cages covered with blankets.

The men on patrol would never hear their pleas for asylum, watching

for floaters, hearts pumping coffee all night on the Texas side of the river.

No one, they say, had ever seen floaters so clean: Óscar's black shirt

yanked up to the armpits, Valeria's arm slung around her father's

neck even after the light left her eyes, both face down in the weeds,

back on the Mexican side of the river. Another edited photo: See how

her head disappears in his shirt, the waterlogged diaper bunched

in her pants, the blue of the blue cans. The radio warned us about

the crisis actors we see at one school shooting after another; the man

called Óscar will breathe, sit up, speak, tug the black shirt over

his head, shower off the mud and shake hands with the photographer.

Yet, the floaters did not float down the Río Grande like Olympians

showing off the backstroke, nor did their souls float up to Dallas,

land of rumored jobs and a president shot in the head as he waved

from his motorcade. No bubbles rose from their breath in the mud,

light as the iridescent circles of soap that would fascinate a two-year-old.

And the dead still have names, names that sing in praise of the saints,

names that flower in blossoms of white, a cortege of names dressed

all in black, trailing the coffins to the cemetery. Carve their names

in headlines and gravestones they would never know in the kitchens

of this cacophonous world. Enter their names in the book of names.

Say Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez; say Angie Valeria Martínez Ávalos.

Bury them in a corner of the cemetery named for the sainted archbishop

of the poor, shot in the heart saying mass, bullets bought by the taxes

I paid when I worked as a bouncer and fractured my hand forty years

ago, and bumper stickers read: El Salvador Is Spanish for Vietnam.

When the last bubble of breath escapes the body, may the men

who speak of floaters, who have never seen floaters this clean,

float through the clouds to the heavens, where they paddle the air

as they wait for the saint who flips through the keys on his ring

like a drowsy janitor, till he fingers the key that turns the lock and shuts

the gate on their babble-tongued faces, and they plunge back to earth,

a shower of hailstones pelting the river, the Mexican side of the river.