Channeling The Electronic Magnetism

“We are actually fourth dimensional beings in a third dimensional body inhabiting a second dimensional world!”― Neal Cassady

The road of the true music artist (of all artists) can be a hard road, a road that walks the tight rope of genius and insanity, of popularity and disfavor: in the world of ever changing, fickle public tastes, with always new generations of enthusiasts embracing evolved sounds and movements, even the greatest artists are faced with the reality that the limelight rarely stays on one stage, on one career. There are so few artists who are resistant to such realities of change, and so many who react to it by attempting to embrace it, to find renewed relevance by infusing their craft with more modern, timely tastes.

The late 60s and early 70s were times perceived as one of the greatest periods of recorded music. Psychedelia. Electric bluesified rock. Funk. Spiritualized Jazz. Swamp Pop. Heavy heavy monster sounds. Inspired recording techniques and a public thirst for mind expansive music was driving through a generation of war and civil rights turmoil. But for many of the progenitors of southern soul…those belters and crooners from the late 1950 and early 1960s who established not only a sound but a genre…it was a time of changing tastes that found their singles no longer charting, their go-to production styles being replaced in the charts by newbies who also called themselves soul singers, but with an evolved type of soul sound.

And thus, in search for relevance, many of the iconic soul singers began experimenting with “now sounds,” different from the sounds that made them famous, which actually led to the production of a gaggle of truly inspired records. Don Covay formed Don Covay and the Lemon Jefferson Blues Band (featuring John Hammond, Jr) producing the enticing, sultry dark bluesy record The House of Blue Lights (a far cry from his to-the-dancefloor Seesaw days). Chubby Checker went for a swampy dark twist with his 1971 Chequered record (Jim Ford fans, pay attention) while Ben E. King stood by a funkier sound with his 1970 album Rough Edges. None of these unique beauties hit the charts, as were their intention, but given time and perspective, they are stand-alone high-water moments in each career and very very much worth a listen.

Solomon Burke, King Solomon, one of the greatest soul singers to ever walk the earth, was also wandering a fallow field in the late 60s. Burke, whose Atlantic records helped define the soul era—whose first million-selling hit was actually on the country chart1 as well as the soul chart, his 1961 cover of Virgil "Pappy" Stewart’s Just Out Of Reach (of My Two Empty Arms)—had left Atlantic and was bouncing around labels. First he signed to Bell, having a hit with his cover of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Proud Mary, recorded while the CCR version was still on its way up the charts, making the song his own, as he always did, as a vehicle to talk about race history in America (John Fogerty sited Solomon’s version as his favorite). But even with the hit, he found himself a’wandering again, signing to MGM, a surprise move given the label was not known for its soul music. But Burke was no longer the popular artist he had been…or would be in the 1990s, as his legend grew for a next generation of appreciators like me.

It was during his tenure at MGM, in a period of two years, 1971 and 72, that Solomon Burke released a trio of records that celebrated a final chapter of his classic period, or maybe a highpoint of a mid-period. They were three commercial failures—some critics opined that they distanced him from his black audience, which constituted a majority of his fanbase. The records have barely been reissued, are not available on any streaming service (do you hear that, Dan Makta?), and can be physically picked up on-line for cheap. They show Burke stretching as an artist…stretching but not breaking…with his signature, powerful voice opening up the heavens.

“Solomon Burke has rattled around MGM music studio for some years now building a solid, though rather unheralded name as an effective soul singer”- Fort Worth Star Telegram, June 24, 1971

This quote (which I was completely stunned to read) is the opening to a review of the first of the three records Solomon Burke released on MGM…the best of the bunch, and one of the best of his career: Electronic Magnetism. Unlike the opening of his previous Bell record, Proud Mary, or any of his Atlantic offerings, Electronic Magnetism opens with a title track bereft of his traditional tight soul band, being replaced with a softer orchestrated sound with strings souring, compliments of Gene Page, better known as Barry White’s arranger.

But that voice of Burke’s reins the whole arrangement in, with a melody that cannot be beat and background vocals that further lift his words to the heavens. Burke’s cover of All For The Love Of Sunshine, which Lalo Shifrin performed on the Kelly’s Heroes soundtrack a year before, is a slight return to form with a little more power and push from the guitar/bass/drum adding sitar highlights throughout like he did on Proud Mary (editor’s note: sooo good to hear Solomon rock the sitar). How was Burke able to take any song by any musician and make it his own? I realize that is the job of a great singer, but Solomon almost steals the publishing credit and the historical perspective with his interpretations. I have never heard an artist do it better. He pulls the same grandeur with another Creedence cover, Lookin’ Out My Back Door, and an Elton John medley. Strangely the more “adult” and arranged sound does not keep this Solomon Burke record from being mighty powerful; it provides a canvas for his tough, huge voice to bleed a hotter red against the angelic hues.

MGM’s next attempt at breaking Burke back into the mainstream came that same year, when Burke composed the soundtrack from Blaxploitation film Cool Breeze. 1971, the year of Isaac Hayes’ Theme from Shaft, from the film of the same name, went to #1 on the Billboard charts…why shouldn’t Burke have the same success. Once again, Burke took the new medium and made a record with some smoking, funky, greazy tracks like The Theme To Cool Breeze (a perfect example of the Blaxploitation sound), Get Up And Do Something For Yourself, and Love's Street And Fool's Road along with some fiery instrumentals. The film did no business, the soundtrack went nowhere. But damn, it is a great listen.

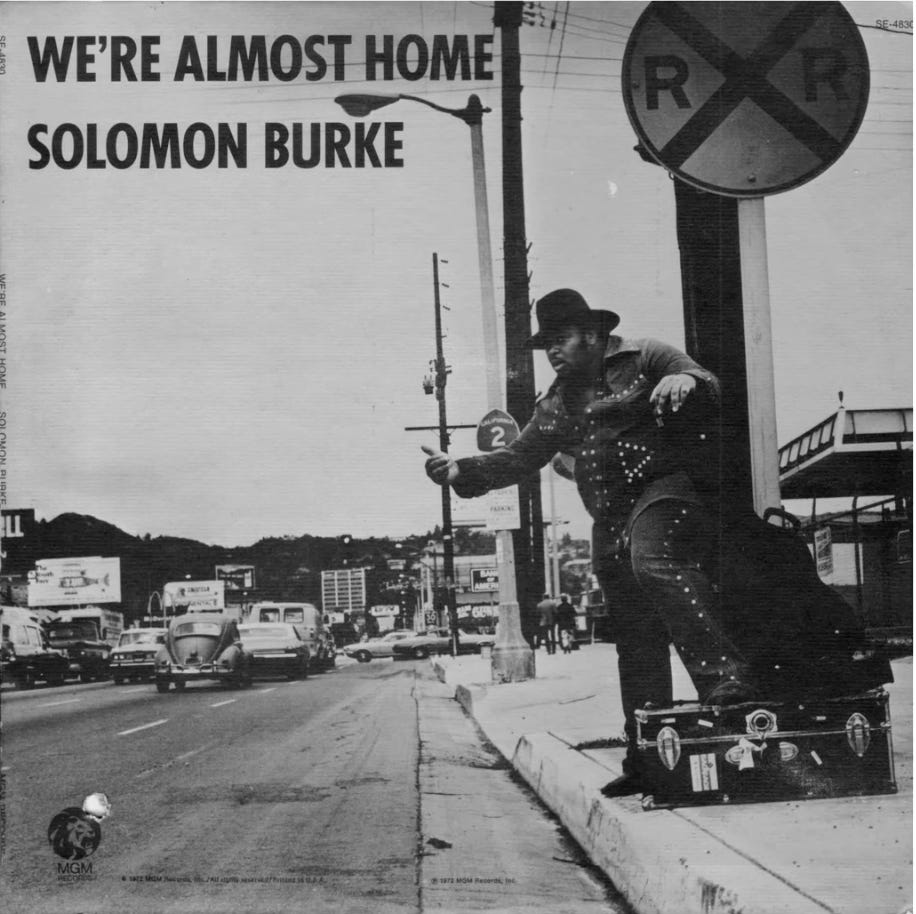

Finally, in 1972, Burke teamed up once again with Gene Page to produce the record We’re Almost Home, the smoothest of the three records. Enter Solomon Burke the crooner, the lounger, the lovers’ rocker. While this is definitely the weakest of the three records, one thing is not at all weak: Burke’s iconic voice which comes across especially well on the few upbeat numbers on the record. On Everything's Going To Be Alright, Very Soon, which displays Burke veering into Isley Brother’s Fight The Power territory, his vocal performance is just as soulful gritty as anything he has done before. Speaking of the Isleys. I Got To Tell It could easily be on one of their early-to-mid seventies T-Neck records. A great groove, and again a great vehicle for Burke’s voice to shine. Those numbers alone are worth the price of admission. The record was released with less fanfare than the ones before and marked the ending of his chapter with MGM.

Solomon Burke bounced around labels for decades. But he never stopped making records and touring. By the time I moved down to Los Angeles in the early 90s, his power….his legacy…was once again legendary and he would soon sign to Anti- records and record his mighty comeback record, “Don’t Give Up On Me.” The House of Blues had built him a throne of painted wood and bottle caps and gave him regular performance slots on their stage; he once again became a fixture in the world of soul. He would pack the House on his nights there, playing with his huge band, singing with his seventh son, handing roses out to the audience members as he would sing his most beloved hits. I tried to never miss a show.

But there was a time in his career, a vast desert of a time, a time that happens to many of the greatest artists, when the hits were not coming, when public favor has quelled. But King Solomon would not be shaken, and in turn produced some incredible records that are now ours to discover.

A Few New-ish Podcasts on Recorded Sound

The Association for Recorded Sound Collections has a robust and active listserve, that people can join even if not a member (but I encourage anyone who is interested to join or are least support). A recent chain started by the question: “What are the best podcasts-on the topic of recorded sound, recorded sound history or preservation or musical history-to listen to these days?” The answers have led me down a path of checking out these truly intriguing podcasts I had no idea existed (there are many others in this field, these are new to me…some being recently started):

Twenty Thousand Hertz: A podcast that spends each episode looking into the sounds around us: recorded sounds (most recently jingles, but also soundtracks, the history of bass sounds in popular music…), sounds around us (they recently ran a great back-to-back podcast translating dog and cat communication) and other sounds (auditory hallucinations, sonic exhibits). A fantastic podcast.

The ARSC podcasts: Two of them. Echoes of History: A super short podcast (2-4 minutes an episode) exploring “authentic, period recordings that help us witness times past like nothing else can” including the first political sound bites and the first weight-loss recordings). Time Collected: A look into the people who oversee sound documents. This podcast only has two episodes thus far, focusing so far on the sounds of Kid Ory and Professor Longhair.

Sound Files: This National Recording Preservation Foundation podcast also goes deep on sound recordings and those in charge of them, the three episodes so far examine Alaskan oral histories, Native American sound recordings and HBCU radio archives.

Sound of the Hound: Even though he did not call himself by either name, Fred Gaisberg was one of the early great A&R men and record producers, helping define the industry. This podcast takes a deep dive into his work.

My friend had something to do with this great initiative…connecting location scouts with home owners to see if they have pictures of their houses for insurance claims. One of the many interesting initiatives to spring up to help people who have been so direly impacted by the fire. Another friend, Brandon Jay, has started Altadena Musicians to help those who lost their music instrument livelihood in the fire. Beautiful initiatives both.

How the guitarist for one of the most famous bands in history disappeared to Texas

From my friend Bill Bentley’s social media comment: “The super-great writer Andrew Dansby jumps into the unique world of Velvet Underground guitarist Sterling Morrison, who moved to Austin after the VU imploded in 1970, and then Houston. It's a totally one-of-a-kind rock & roll tale, and Sterling was unequaled in his own history. We got to be friends in Austin in 1974, played together in the Bizarros there for a few years, split apart and came back together in Paris when the VU regrouped for a celebration in the early 1990s. What a time it was, and Dansby catches it all. Sterling became a tugboat captain in the Houston Ship Channel in the '80s, and died in 1995 from non-Hodgkins lymphoma. I've never met anyone remotely like Holmes, which was his first name and one he would sometimes go by, and miss him everyday. His story still fascinates me, and I will always miss him.” (CLICK FOR THE NEXT ARTICLE)

Read the Introduction to Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror

…and history repeats itself. We do not learn.

Wrong Norma

By: Anne Carson

Famously, southern concert bookers did not know Burke was black and booked him to play at KKK rallies and other deeply white/Southern venues. As Beyoncé becomes the first ever black artist with win the Best Country Album of the Year, it is nice to think of who paved the way before her…and to celebrate such barrier breakers.

Another very intruduing issue, David, great to see Dansby's Morrison exploration, guess you know he retired from the Chronicle, as of 1.1.25. Also, if you didn't know, Robert K. Oermann is close to finishing his book on blacks in country music.