Dreaming with Mark Fry

“I looked at the clock with the faint unconscious hope...that time will somehow have passed magically away and the next time you look it will be bedtime.”― Shirley Jackson

Mark Fry’s Dreaming with Alice is a legendary record….

a defining example of the psychedelic folk sound from the late 60s/early 70s. The sweet song meditations basked in foggy reverberations are of another world and Fry a mystical troubadour whose subdued style seems mere smoke from the pipe of the Caterpillar in Wonderland.

In the pre-internet world, a record like Dreaming with Alice was an unsolvable mystery for anyone lucky enough to hear it. And given that before the year 2000, the only available copies were the super-obscure first pressings from 1972, finding someone who owned a copy could be difficult (thank you Geoffrey Weiss for originally playing it for me). When the first verse of the title track floats through the speakers, with its beautiful guitar meandering and surreal lyrics, you are immediately thrown into a dream akin to those described by Fitz Hugh Ludlow in the 18th century, magically carpeting to the lands that only Alice had ventured before.

Who was this dreamer, Mark Fry? The late-night whiskied storyteller told of a teenager in the early seventies who journeyed from England to Italy where he produced this record for a major label. But how did that go down and what happened after? The record was birthed into obscurity and Fry just seemed to disappear. All that remained was this moment of musical brilliance.

But Dreaming with Alice was only the beginning of Fry’s artistic story. He has since gone on to become a distinguished painter while continuing to record. The modern-day searchable world makes it easy to find his website, that includes a video where you can see the paintings he is working on as well as his recording studio. Streaming services feature not only his classic record but also more modern releases like the beautiful, lush South Wind, Clear Sky and singles he released over the past year. The only mystery still left is how his voice sounds the same as it did almost fifty years ago…

Mark and I had corresponded a few times over the years, and I reached out to see if he would not mind answering some questions touching upon what he is currently focused on as well as some about his past...including about that dream of a record that becomes more legendary with the passing of time. The following is what he had to say (I recommend listing to his music while reading on….).

DAVID: You mentioned to me in our initial correspondence that you were focusing on your painting at the moment. AND you have talked about how your visual art and your musical art are pretty intertwined with one another. Is that still the case? Does one feed the other?

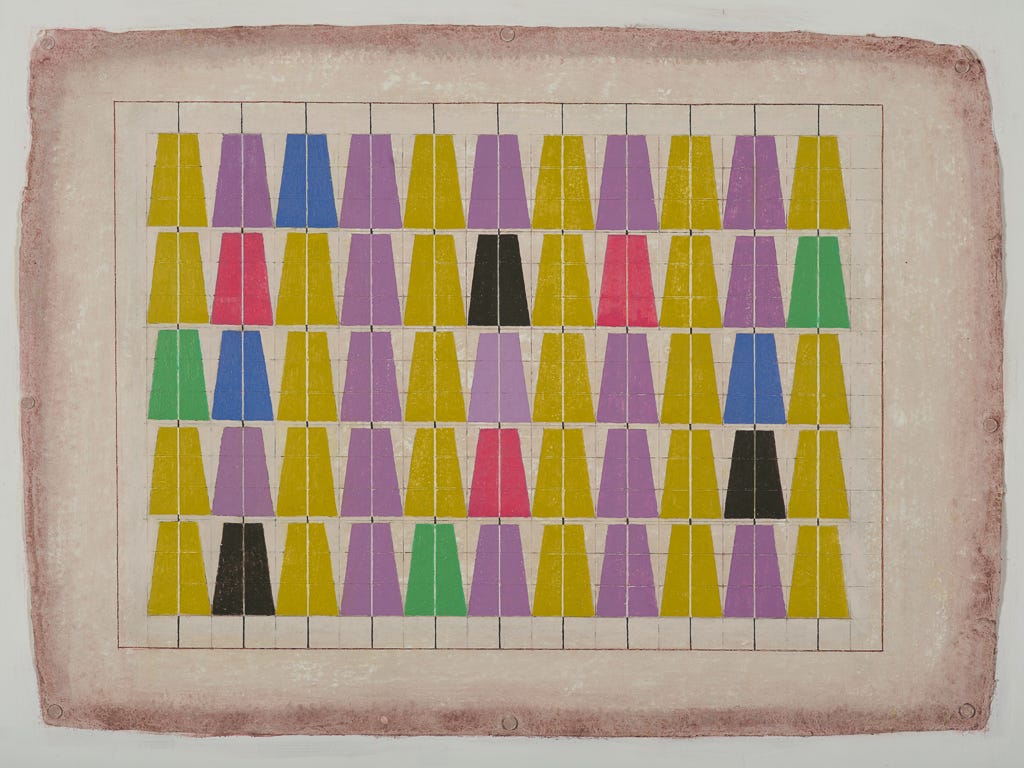

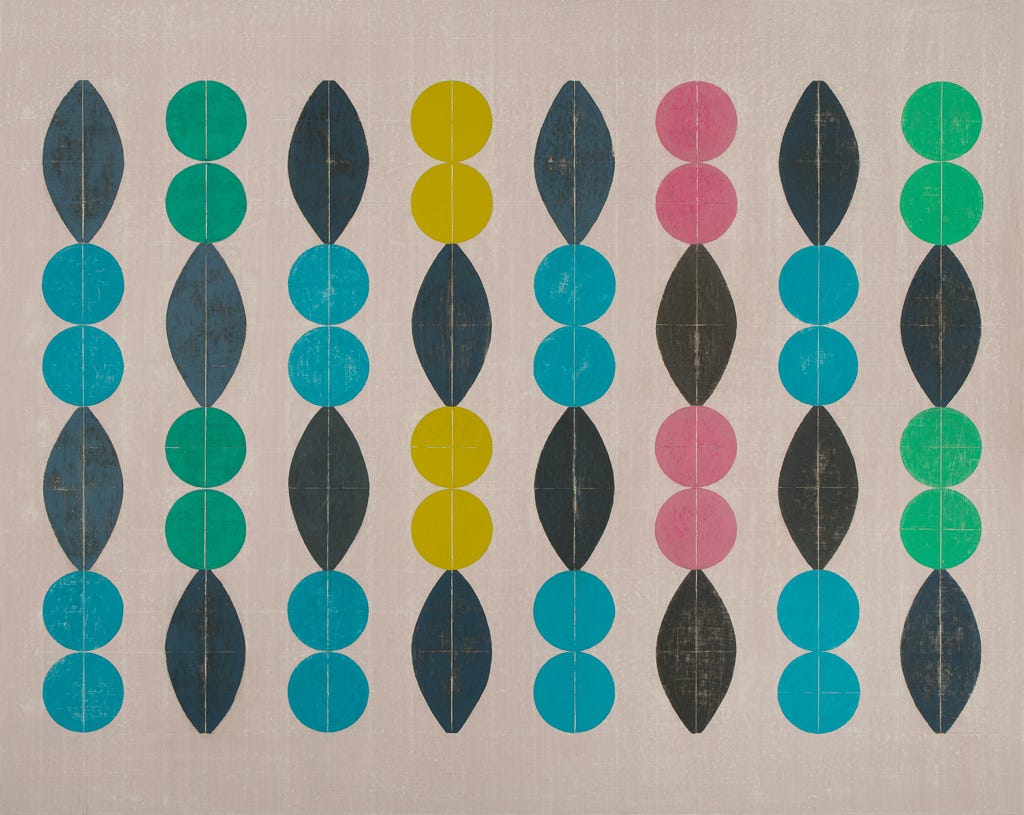

MARK: Yes, they are pretty intertwined, but I'm not sure if they directly feed one another; sometimes it feels as though one is starving the other. It's a little like juggling two balls, one is always out on its own suspended in the air, and the other is in your hand. There are many common pursuits in the making of a painting or a song. Harmony, colour, balance, repetition, the challenge of trying to tell a story in a confined space. I've always liked what Ray Davies said about the three-minute single, that it was "one of the greatest art forms of the twentieth century". I have a sense that, as my painting has become more abstract over the years, I have grown more relaxed about not trying to get a lyric to make too much sense, in a linear way. That seemed to come naturally when I was young. So I would say that one informs the other.

DAVID: You come from such a family of artists and art appreciation…and you are falling right into the family tradition. Was there one family member that had a major impact on you as a developing artist (or maybe a family friend who was around as you grew up)?

MARK: Although my father was a very successful painter, it was my mother's artistic voice that I was most influenced by as a young boy. She was a very fine artist in her own right, but I think she found it difficult raising two young children on her own and pursuing a painting career. I think she also might have felt overshadowed by my father's success. I wish she had painted more, she died tragically young. She was musical too, and we used to play little Bartok pieces together for cello and piano. Me on cello, my mother on piano. We used to watch Top of the Pops together on the BBC, she loved Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles and Joan Baez. She bought me records. She took me to see Ike and Tina Turner and The Ikettes at the Middle Earth club in London, I think I was 13 or 14. As you can imagine that made a huge impression on me.

Painting was all around me from a very early age. My father won a Harkness fellowship in 1960, which meant he could work in the U.S. for two years, and so from a very early age I was aware of artists like Rothko and Alexander Calder. I spent a lot of time when I was young making mobiles that didn't really work!

You never forget those first very early seeds that are sown. I remember overhearing a boy at prep school rehearsing the French horn (I was nine years old) behind a closed rehearsal door. There was a beautiful loneliness at work in that room, he had a consoling and magical friend in his instrument, and I knew at that moment that I wanted to be a musician too.

Much later on, when I had just left school and was living in Italy, I fell in love with an Italian woman twice my age. She was an enormous influence on my life and gave me the artistic confidence to record the songs I was writing in Florence and to make a record, which would become Dreaming With Alice.

DAVID: Beyond family and friends: Your lyrics have always had a slightly surreal quality to them….your sound in general has a beautiful outer-worldly feeling. In the recent Pink Floyd exhibition, there was a room that showed how Syd Barret took from children’s books he grew up with as inspirations to his style. Were there artists or works of art you came across that inspired you? Helped you realize the musical artist you became?

MARK: There were so many visual and literary tributaries that fed into the river at the time. I was very influenced by the paintings of Samuel Palmer when I was a teenager. Apart from the beauty of the work, I think I was also drawn to the narrative, the way he often painted by moonlight; there was something so romantic to me about that at the time, working alone under a big summer moon. The Pre-Raphaelites were also an influence at the time, and the Narnia books by C.S. Lewis, especially The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe. It was that idea that you could pass from one place into another through a magical door. Maybe it's that idea that is at the core of being an artist, the possibility of transformation. In 1966 Jonathan Miller made a modern and quite psychedelic film adaptation of Lewis Carroll's Alice In Wonderland for the BBC, with music by Ravi Shankar1. I think this must have seeped deep into my visual and musical library as well.

DAVID: By the sound of it, you are pretty self contained when making a record…having your recording studio a part of your overall artist studio. And yet, recordings like the ones that make up South Wind, Clear Sky are so lush..so orchestrated, so highly arranged. How do you go about the recording process?

MARK: When I have a song which I think is ready for recording, I'm careful not to be tempted into finalising everything too early, like framing a painting before it's finished; speaking personally, I have never found that a good idea. I start by recording some simple guitars to a click track on my little eight-track recorder, and then I add the lead vocal and any additional vocal harmonies. At this point I invariably begin to over-decorate/over-paint the song. At a much later stage I will take the songs to a producer and in a professional studio we will start to scrape off what is superfluous and begin to build up again from the essential, bringing in other musicians along the way. It's a very similar process to making a painting. On my last album Like A Hummingbird's Shadow (which hasn't been released yet, due to the pandemic) we pretty much started from scratch and ended up in Peter Gabriel's Real World Studios with a colliery brass band from Wales. It was a wonderful journey.

DAVID: It seems like the legend of Dreaming With Alice keeps growing with time. Is that surprising to you? How do you see that record as a piece of your life’s work?

MARK: I must say I didn't think the interest in Dreaming With Alice would persist in the way it has - as you say, it just keeps growing. It endlessly surprises me in the most delightful ways, working with young musicians, being invited to play in festivals here and there around the world. If people were only listening to Alice and none of my newer songs, I think that would be slightly depressing, but Alice has kept me on my musical toes, and fans are discovering more of my catalogue.

I am really happy with the Now-Again release of Alice which was remastered from the original masters by Bernie Grundman in L.A. It's a kind of miracle that the masters turned up intact and ended up in the good hands of Eothen Alapatt at Now-Again, it's the definitive re-release.

DAVID: What are you reading and listening to these days?

I became a ridiculously late discoverer of Bill Callahan, I think I tumbled upon him in the NPR Tiny Desk sessions. I've become a huge fan, I think he's a very original artist. There's something naked and unflinching in his writing, he's a poet really. I'm also a big fan of Big Thief and Adrianne Lenker, she's a beautiful songwriter.

Funnily enough the last couple of books I read were both American writers: 'Travels With Charley' by Steinbeck and 'Life Among The Savages' by Shirley Jackson.

DAVID: Over the last few years you have released a few singles…are there any music projects in the future we can look forward to?

MARK: Next year I'm hoping to find someone to release my new album Like A Hummingbird's Shadow, which I recorded just before the pandemic, with Nick Franglen producing. I also recorded an EP, In Our Heavenly World, during lockdown with a wonderful musician, Iain Ross. We obviously couldn't move around in the lockdown, so I sent him some new songs from France (where I live), and he arranged and played all the instruments in his studio on his narrowboat on the river Lea in London. We played musical ping-pong and defeated the travel bans.

So yes, I hope there will be some new work seeing the light of day next year.

DAVID: Has there been a silver lining to this Covid period?

MARK: Yes, with almost no aeroplanes in the sky last year, you could actually see the silver lining...

Jonathan Miller’s film is also included in the recent Pink Floyd exhibit “Their Mortal Remains” as an influence on Syd Barrett